Learning Objectives

- Learn the Canine Teeth Anatomy

- Define Periodontal Disease

- Understand the Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease

- Identify the Clinical Signs of Periodontal Disease

- Learn ways to combat periodontal disease.

Teeth

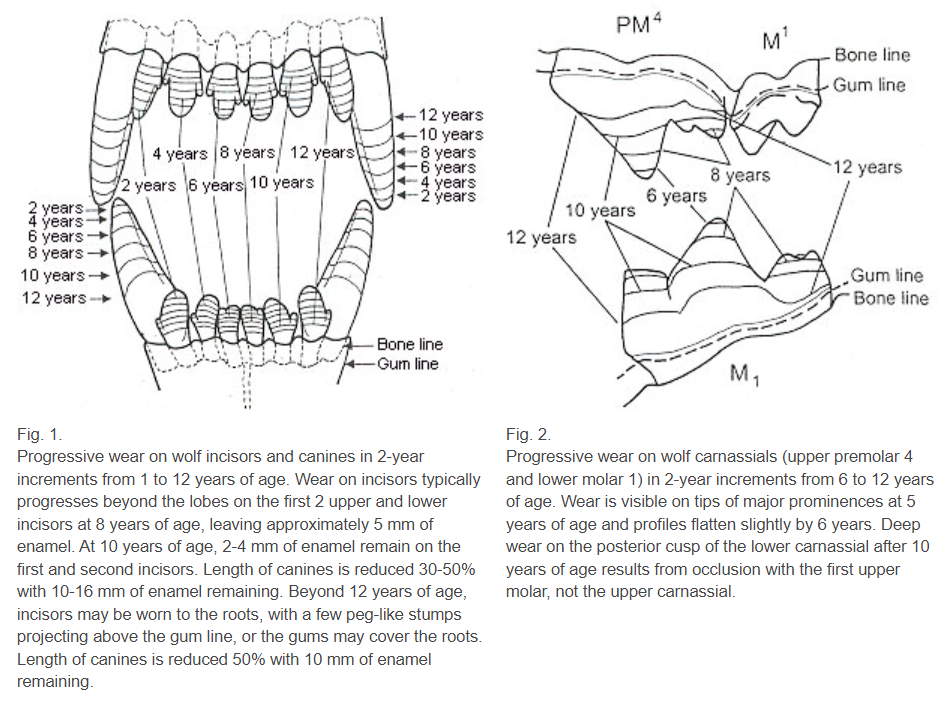

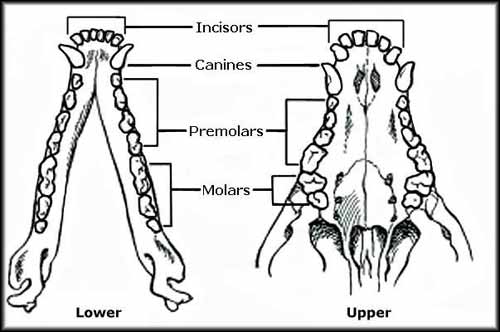

Dental formula – the number and types of teeth that should be found in a normal mouth is unique to every species. There are two sets of teeth in mammals, namely deciduous and permanent. The four types of teeth in dogs and cats each have particular functions.

Since most domesticated dogs are given commercial diets, evolution and adaptation changed the way pet dogs used their teeth compared to their wild ancestors. Initially, incisors were used to cut, pick up, and groom; canines were used to rip, tear, and hold; premolars and molars were used to grind. The largest chewing teeth in cats and dogs are called carnassials, the upper fourth premolar and lower first molar.

Deciduous Dental Formula (puppy teeth):

Maxilla: 6 incisors, 2 canines, 6 premolars

Mandible: 6 incisors, 2 canines, 6 premolars

Total: 28

Permanent Dental Formula (adult teeth):

Maxilla: 6 incisors, 2 canines, 8 premolars, 4 molars

Mandible: 6 incisors, 2 canines, 8 premolars, 6 molars

Total: 42

Gingiva

The soft tissue surrounding and supporting the teeth and covering the alveolar bone is the gingiva—usually, pink in color and smooth. The mucogingival junction connects the gingiva to the rest of the oral mucosa of the lips. Gingival tissue attached to the tooth protects the bone and tooth-supporting structures from infection, trauma, and periodontal disease. The gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket is between the free gingiva and the tooth. This gap usually is 3mm deep in dogs. Pockets that exceed these depths are indicative of connective tissue loss. Pockets are frequently connected with gingivitis—a kind of periodontal disease that occurs early in the disease's progression.

Anatomy of the Tooth

Teeth are divided into two generations (diphyodont) in dogs and cats. Dentin makes up the majority of a permanent tooth, with the pulp chamber comprising blood vessels, nerves, lymphatics, connective tissue, and odontoblasts located in the center of the tooth. Gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone comprise the periodontium—the tooth-supporting tissues. The periodontal ligament, attached between the cementum and the alveolar bone, secures the tooth in the alveolus.

Teeth are divided into two sections: (a) the crown or the section of the tooth above the gum line, is responsible for holding, tearing, and chewing; it is coated with a thin layer of enamel—a firm, nonporous material comprised mainly of the mineral hydroxyapatite; and, (b) the root secures the tooth to the surrounding bone. It is encased in a dense connective tissue known as cementum.

Crown

The crown, mainly composed of enamel, is the section of the tooth above the gumline. The cusp is the topmost of a crown. It meets the root at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), commonly called the "neck" or "cervical line". Crowns are prone to abrasion, fracture, and staining due to excessive chewing, trauma, and tetracycline use in growing animals. When there is a hemorrhage inside the pulp, the damaged tooth appears pink to red. If not treated, the tooth may die. As a result, the crown will become purple, gray, or black.

Enamel

Enamel, comprised mainly of minerals with a trace of water and organic substances, making it solid and fragile at the same time, is the material that covers the crown. It is lustrous and comes in various colors, ranging from white to ivory. Enamel chip fractures can happen when pets chew on hard objects such as rocks and bones. Because of lack of blood flow, it cannot heal by itself. In adult dogs, the depth is around 1mm, while in younger ones, it cracks quickly because of its fragility and wide underlying pulp chamber.

Cementum

The root is covered by a mineralized connective tissue called cementum. It starts from the CEJ, continuing apically. Cementum, in contrast to enamel, is drab and pitted. It is softer than enamel, dentin, and bone because of its lower mineral concentration. Periodontal ligament collagen fibers penetrate the cementum to help retain the root in the alveolar bone. The connective tissue of the cementum allows it to restructure and repair itself over time.

Dentin

Dentin, which is porous and yellow, is the primary component. It comprises 70% inorganic material and 30% collagen fibers and water. Dentin fill in the pulp cavity of a living tooth, which is made up of odontoblasts (odonto meaning tooth and blast meaning germ or embryo). With age, the pulp cavity/root canal narrows because of the continuous laying down of odontoblasts. Dentin is classified into three categories. Before a tooth emerges, primary dentin develops. After eruption and during life, secondary dentin forms. The production of tertiary dentin is triggered by dental trauma. The tooth-repair substance may be brown or deeper yellow than the surrounding tooth structure.

Pulp

The pulp or endodontic (endo meaning inside and dontic meaning tooth) system is made up of veins, arteries, lymphatic vessels, nerves, odontoblasts, and other cellular parts. At the tip of the tooth, the pulp chamber meets the periodontal ligament. The components of the pulp, veins, and arteries keep the tooth alive, and nerves transmit pain in response to trauma. Odontoblasts create dentin in the pulp. Pulp inflammation or death can result from early damage to a tooth which could lead to a stop in odontoblast production and a large pulp chamber.

Roots

The live tissues are found in the root, primarily made of dentin and coated with cementum. Unlike humans, the apical delta of a dog's or cat's tooth is made up of multiple holes that lead to the pulp chamber or root canal. During endodontic (root canal) therapy, the significance of the apical delta becomes clear.

Table 1. The Number of Tooth Roots in Dogs

| Teeth | Maxilla | Mandible |

| Incisors | 1 | 1 |

| Canines | 1 | 1 |

| First Premolar | 1 | 1 |

| Second Premolar | 2 | 2 |

| Third Premolar | 2 | 2 |

| Fourth Premolar | 3 | 2 |

| First Molar | 3 | 2 |

| Second Molar | 3 | 2 |

| Third Molar | Absent | 1 |

Periodontal Ligament

The periodontal ligament connects the tooth cementum to the alveolar bone and adjacent teeth. It is mainly composed of collagen fibers, blood vessels, nerves, and elastic fibers, and the fibers resist chewing, damage, and extraction pressures. The ligament's flexibility facilitates regular tooth movement. Unlike the nerves of the pulp cavity, the periodontal ligament nerves transmit pressure, heat, and cold stimuli.

Gingivitis is a progressive disorder that leads to periodontal disease, the most frequent illness in dogs and cats. Periodontitis or periodontium inflammation damages the periodontal ligament, gingiva, bone, and tooth loss. The prognosis is good if caught early.

Table 2. Deciduous Teeth Eruption

| Tooth | Week of Eruption |

| Incisors | 3-4 |

| Canines | 3 |

| Premolars | 4-12 |

| Molars | None |

Deciduous Teeth

Dogs and cats are diphyodont -- have two sets of teeth throughout their lives. The roots of deciduous teeth are absorbed, loosen, and fall out when the permanent teeth erupt. Most rodents and lagomorphs have open-rooted teeth that continue to develop throughout their lives. Many snakes and sharks are polyphyodonts – teeth continually replaced.

Permanent Teeth

Primary teeth do not fall out or erupt simultaneously as permanent teeth. In most cases, the primary tooth is lost as the permanent tooth erupts. The primary tooth is retained if this does not occur. Two teeth should never share a space. Rotation and malocclusion of the permanent teeth result from retained primary teeth, which precludes regular tooth cleaning. This then results in food accumulation leading to periodontal disease, which can cause damage to a permanent tooth and possible tooth loss.

Tooth eruption is influenced by sex, breed, general health and well-being, body size, and birth season. Females, bigger breeds, summer-born, and healthy animals have teeth that emerge sooner than males.

Table 3. Permanent Teeth Eruption

| Tooth | Month of Eruption |

| Incisors | 3-5 |

| Canines | 4-6 |

| Premolars | 4-6 |

| Molars | 5-7 |

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease, an inflammatory disease that includes two stages: gingivitis and periodontitis, is a common disorder in companion animals. It is associated with odontalgia, halitosis, ulceration, and tooth loss.

The early or reversible stage, gingivitis, results from the formation of microorganisms in the dental plaque on the teeth surface. Inflammation is limited to the gingiva and might be reversed with consistent homecare or dental prophylaxis. Symptoms include red and swollen gums that bleed easily. This may develop into periodontal disease if not treated.

The later or irreversible stage, periodontitis, is the inflammation of deeper structures, including the periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. This could lead to loss of periodontal tissues then tooth loss. Some of the symptoms are root exposure, furcation exposure, or loose tooth. This stage is usually associated with bacteremia that may affect systemic organs involving the cardiovascular, kidneys, and lungs.

Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease

Pellicle

The moist condition in the mouth is caused by saliva—a liquid produced by the salivary glands to lubricate the mouth and help in digestion. It creates a pellicle which is a thin layer composed of salivary proteins and glycoproteins on the teeth. Within a few hours, several strains of bacteria like Actinomyces and Streptococcus begin to bind to the pellicle to feed on amino acids, proteins, and glycoproteins.

Dental Plaque

Gram-positive, non-motile, aerobic cocci make up most of the microorganisms on the tooth surface. As bacteria colonize the pellicle, a soft, sticky biofilm develops on the crown. In the absence of frequent teeth brushing, the biofilm encased in a matrix comprises salivary glycoproteins and extracellular polysaccharides, which continually coat the tooth surface. In addition to bacteria, plaque is made up of epithelial cells, white blood cells, and macrophages.

As aerobic bacteria use oxygen and grow, the biofilm thickens, allowing anaerobic bacteria to thrive in the environment. The bacterial biofilm gradually infiltrates the sulcus between the gingiva and the tooth, providing an environment that favors gram-negative bacteria that are more damaging.

The transition from a gram-positive to a gram-negative population causes periodontal disease, not an increase in the number of bacteria. A shift in bacterial species causes the onset of gingivitis.

The gum tissue loses its capacity to hold close to the tooth's surface as it swells. This results in a periodontal pocket between the tooth and the gingiva. Periodontal disease is evident when the pocket depth in a dog's mouth is larger than 3 mm. Plaque may now migrate past the gum line, allowing germs to destroy the tissue supporting the tooth. The bacteria also release chemicals that help the biofilm adhere to the tooth and shield the bacteria from antimicrobial treatments; bacteria identified in plaque might be 1000 times more resistant to antiseptics and antibiotics than the same bacteria alone.

The release of biochemical mediators, including cytokines, prostaglandins, and matrix metalloproteinases, primarily responsible for the gradual tissue deterioration observed in periodontitis, is triggered by dental plaque in the gingival sulcus.

Supragingival plaque is evident on the visible tooth surface, while subgingival plaque is defined as plaque that spreads beyond the free gingival edge and into the gingival sulcus. In the early phases of periodontal disease, supragingival plaque is likely to influence the pathogenicity of subgingival plaque. The impact of supragingival plaque and calculus is minimal after the periodontal pocket has formed. As a result, reducing supragingival plaque alone is unsuccessful in slowing periodontal disease development.

Dental plaque is soft and colorless, but it hardens and produces dental calculus when calcium salts and other minerals from the saliva are deposited. Heavy plaque deposits might appear as a soft grey or white substance. Dental calculus is not damaging, but it aids in attaching new dental plaque.

It's vital to remember that tooth plaque is the cause of periodontal disease, not the illness itself. When white blood cells consume bacteria, they rupture – releasing toxins and enzymes that irritate the animal's periodontal tissues, causing gingivitis which develops when plaque is accumulated. This happens when the gingiva mounts an immune defense by increasing its blood supply leading to redness and swelling. Plaque may only be removed from the teeth via mechanical scrubbings such as brushing, abrasive diets, or professional dental cleanings after it has been attached. Periodontitis might develop if the chronic inflammatory host response is not addressed.

Dental Calculus

Dog's mouth is slightly alkaline (basic), creating an environment where calcium salts are more likely to be accumulated. The salivary fluid contains calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate salts. These calcium compounds form crystals on the teeth's surface and mineralize soft plaque. Because oxygen is low or absent, anaerobic bacteria thrive in the deep cracks along the calculus surface.

If plaque is not cleaned, calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate salts in the saliva begin to mineralize and form calculus or tartar within 24-72 hours. Although calculus does not cause periodontal disease, it is dense, hard, and porous, enabling bacteria to thrive inside and underneath it. It is securely bonded to the tooth and can only be removed mechanically. Calculus deposits may become so enormous that they displace the gingiva and cause harm.

Calculus is largely non-pathogenic, mainly acting as an irritation. The bacteria in the subgingival plaque produce toxins and metabolic products that cause gingival and periodontal tissue irritation. Gingivitis develops due to this inflammation, which damages the gingival tissues. As a consequence of the inflammation, periodontitis might develop.

The bacterial metabolic byproducts cause tissue damage and an inflammatory reaction in the animal. When vascular permeability and space between the crevicular epithelial cells widen, white blood cells and other inflammatory mediators travel out of the periodontal soft tissues towards the periodontal space. These enzymes will irritate the fragile gingival and periodontal tissues if discharged into the sulcus. Bacterial virulence and immune response affect the severity of periodontal disease. Often, the host response damages the periodontal tissues.

Gingivitis

Gingivitis or gingival inflammation is the first stage of periodontal disease caused by bacterial plaque. Plaque spreads subgingivally, causing irritation and gingivitis due to bacteria and cell breakdown products attacking the periodontal soft tissues. But, the depth of a sulcus is typically normal.

Gingivitis is reversible, which means that the inflammation goes away after the bacteria-laden dental plaque is eliminated from above and below the gingival edge. Furthermore, it may be avoided by practicing good dental hygiene and removing plaque.

Gingivitis does not always lead to periodontitis. In individuals with local or systemic disorders, gingivitis might grow more severe.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis, the inflammatory damage of the epithelial barrier protecting the support structure of teeth, results in tooth attachment loss since the irreversible loss of tissues develops to alveolar bone loss from periodontal ligament attachment loss.

The tooth support system includes gingiva, cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Bacteria can penetrate the epithelial barrier because the immune system cannot mount an adequate response effectively. The bacteria run out of oxygen as it penetrates deeper into the periodontal tissues and causes more harm. The gingiva separates from the alveolar bone when the epithelial barrier breaks down, resulting in a periodontal pocket or gingival recession; then, the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone are damaged when the infection advances closer to the root. Tooth mobility will become more apparent when more of these support components are compromised.

Pathogenic microorganisms induce immunological and nonimmune responses in the body, resulting in tissue damage. The tissue damage is caused by the host's reaction to plaque bacteria, not the bacteria's pathogenicity. So, although pets will acquire plaque, not all of it will progress to periodontitis. Breed predisposition, malocclusion, chewing habits, systemic health, and local irritants are all variables that might influence the onset and severity of periodontal disease.

Clinical Signs of Periodontal Disease

- Halitosis (Bad breath)

- Gingivitis (red, inflamed)

- Increased drooling

- Blood in saliva

- Pawing at the mouth

- Difficulty eating

- Gingival recession

- Purulent discharge

- Facial swelling

- Nasal discharge

Contributors to Periodontal Disease

- Crowded teeth

- Food and microorganisms may quickly become stuck between teeth, resulting in plaque buildup. Tooth crowding is caused by retained deciduous teeth, dental or jaw malocclusions, and supernumerary teeth frequently in smaller and brachycephalic breeds.

- Fractured, painful, or missing teeth

- It promotes periodontal disease when an animal's mouth has a missing tooth on one side or is painful; it will chew on the other —the lack of self-cleaning caused by chewing results in plaque build-up on the non-chewing side of the mouth.

- Enamel hypocalcification

- Enamel loss or roughening caused by high fever or sickness in juveniles promotes plaque adhesion to teeth.

- Malnutrition and physical or psychological stress

- Some disorders can cause immunodeficiency, and others, including diabetes, may reduce peripheral circulation, lowering the immunological response in the gingiva. Untreated periodontal disease has been linked to poor blood glucose control in people with diabetes; hence treating periodontal disease may assist manage diabetes.

- Excessive levels of corticosteroids, either from medications or health conditions

- This can suppress the immunological response of an animal by reducing white blood cell counts and activity. It may also induce alveolar bone osteoporosis, gingival collagen degeneration, and periodontal tissue damage.

- Other factors

- These include insufficient chewing, abnormal oral anatomy, poor saliva quality, or conditions that can reduce saliva quantity, like keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) and chronic renal failure.

Health Problems Associated with Periodontal Disease

- Oronasal fistulas

- Oronasal fistula (ONF) is the most common local result of periodontal disease. It affects the palatal surface of the maxillary canines, which are separated from the nasal cavity by a thin bone. Any maxillary tooth can be affected. This results in oro-nasal communication causing persistent inflammation.

- Old, small breed dogs especially chondrodystrophic breeds like Dachshunds, are predisposed, but it can happen in any breed.

- Some of the clinical signs are chronic nasal discharge, sneezing, and occasional inappetence and halitosis.

- General anesthesia is often required for a definitive diagnosis. A periodontal probe is inserted into the periodontal space on the palatal surface of the tooth.

- An ONF treatment involves tooth extraction and mucogingival flap closure of the defect.

- Pathologic jaw fractures

- Due to severe periodontal disease, bone loss occurs mainly in the mandible, especially around the roots of canines and first molars. This is common in small breed dogs since the teeth are larger in proportion to their jaws, particularly the first molar in the mandible. Fractures can result from trauma, chewing, playing with toys, or during tooth extraction.

- Prognosis is guarded because of a lack of remaining bone. There are several treatment options, but the diseased roots must be extracted for healing to occur regardless of the method.

- Osteomyelitis

- Osteomyelitis, a portion of dead infected bone, is one of the possible results of chronic periodontal disease. Dental problem is the leading common cause of oral osteomyelitis. When this condition reaches necrosis, it will not respond to antibiotic therapy. Thus, surgical removal of the infected area might be required. Secondary to osteomyelitis, septicemia may also occur.

- Class II peri-endo lesion

- Another possible result of severe periodontal disease is class II peri-endo lesion which occurs in multi-rooted infected teeth. When periodontal loss progresses apically and reaches the endodontic system, it causes endodontic disease through bacterial infection. The infection spreads further and causes periapical ramifications on the other roots. In comparison to class II, class I lesion extends from the root canal system, and class III are combined lesions which is very rare.

- Blindness

- Since the root apices of the fourth maxillary premolar and molars are located proximal to the optic tissues, inflammation near the area can cause blindness.

Dental Homecare

Dental home care is vital in preventing dental problems and diseases. Within twenty-four hours, bacteria attach to the crown to create plaque build-up. Without home care, gingivitis reoccurs, and periodontal pockets become reinfected within two weeks after prophylaxis.

Home care is categorized into two types – active and passive. Active home care includes brushing and oral rinsing, while passive home care includes dental diets, treats, chews, water additives, and dental sealants. Options are oral rinses with chlorhexidine, dental sealant application, and passive methods like dental chews and treats.

Dental diets are divided into chemical and mechanical, which is based on their mechanism. Chemical home care products are usually coated with sodium hexametaphosphate (SHMP) – a chelating agent that binds with calcium in saliva, aiding in calculus formation. This includes mouth wash, gel, and water additives. On the other hand, mechanical products work by physical contact on the tooth surface, actively disrupting plaque formation. This includes dental foods, chews, treats, bone, and brushing.

Tooth Brushing

Preventing inflammation requires mechanical plaque removal at the gum line; thus, brushing should be started slowly and early to avoid dental problems.

Daily brushing is the best home care method for maintaining periodontal health and plaque control, and it is considered the gold standard. It may also prevent existing dental diseases from progressing.

The frequency of brushing depends on dental cases. In severe problems, prophylaxis or treatment is recommended before starting home care to avoid aggravating the pain and discouraging the pet and owner. In pets with clinically healthy gingiva, brushing every other day has been considered beneficial and suggested as sufficient for maintenance. However, pets with gingivitis are required to brush once daily as beneficial effects increase with frequency.

In general, daily brushing is ideal for all pets. On the other hand, occasional brushing has minimal to no impact because bacterial colonization starts within a few hours after cleaning, and mineralization of plaque into calculus may start in 2-3 days without brushing.

Though not necessary, toothpaste is flavored and helps make more enjoyable experiences for pets. In addition, human toothpaste contains xylitol and fluoride, making it toxic for pets. A soft-bristled toothbrush with the right size is ideal since finger brushes are not as abrasive and expose the owner to getting bitten, making it suitable for beginners.

How to Brush the Teeth

- Select a time. Start slowly and gently. Create a daily routine for your pet.

- Acquaint the dog with the process. Start giving the toothpaste at the same time and place and by the same person every day. This causes the pet to anticipate the toothpaste as a treat. Before long, they will be looking forward to their treat. While giving them the toothpaste, touch the face and muzzle.

- Introduce brushing

- Start brushing

- Make it a pleasurable experience

Diet in the Development of Dental Disease

The most important element determining the development of gingivitis and periodontal disease is the presence and persistence of undisturbed plaque on tooth surfaces. As a result, periodontal disease prevention relies heavily on management and feeding habits that reduce plaque and calculus production or help in their removal.

Some of the crucial factors that dictate the development of dental diseases would be frequency with which teeth are brushed, the sort of diet supplied, whether table scraps or non-commercial items are fed, and how often chew toys, dental chews, and biscuits are given.

Once plaque has accumulated on the tooth's surface, it is best removed mechanically by abrasion which may be caused by diet, teeth cleaning, or chewing on chew toys or treats. Chemical agents like rinses, pastes, and sprays may aid, but they won't replace the required abrasion.

The antibacterial agent chlorhexidine digluconate helps reduce odor, plaque formation, and gingivitis in dogs. Chlorhexidine and other antimicrobial products, on the other hand, are far more effective when used in combination with brushing. A chemical mouthwash or gel will not remove the hardened calculus that develops when plaque is formed. As a result, a method that involves regular and consistent mechanical plaque and calculus removal is suggested.

Type of Food

The diet can affect the oral environment in many ways, including tissue integrity, plaque bacteria metabolism, salivary flow and composition, and contact on tooth and mouth surfaces. In small animal practice, it is a presumption that giving dry kibbles reduces plaque and calculus, whereas canned foods increase plaque development. Biting on a hard kibble should clean the teeth due to the crushing movement. Furthermore, since dry food leaves less residue in the mouth for oral bacteria to feed on, plaque builds up slowly. Despite this, many animals given commercial dry foods develop plaque and calculus, and periodontal disease.

According to one research, dogs and cats that ate soft foods had more plaque and gingivitis than those who consumed a higher-fiber diet. In other trials, wet meals had a comparable impact on plaque and calculus buildup as a conventional dry diet. Finally, ordinary dry meals disintegrate at the incisal border of the teeth, offering little to no cleaning at the gingival margin, which is crucial.

When it comes to dry diets, the kibble's size, texture, and content have a significant effect on the mouth, such as plaque bacteria alteration, tooth cleaning, and tissue integrity maintenance. Dietary fiber also helps exercise the gums, improve gingival keratinization, and clean the teeth. Dietary fiber may affect plaque and calculus buildup; however, most regular kibbles break and crumble when the pet bites, providing little to no mechanical cleaning.

According to current evidence, soft meals, such as canned commercial diets or home-prepared foods, seem to be less successful than firm, dry foods in delivering the abrasion required to eliminate plaque that naturally accumulates on teeth. However, giving typical dry pet food does not completely prevent the development of gingivitis and periodontal disease since most studies found that a significant number of animals on dry diets still exhibited symptoms of progressive dental disease.

Natural Diets and Raw Bones

Rawbone supporters argue that giving raw bones to dogs improves the pet's dental hygiene. Furthermore, it is occasionally claimed that feeding commercial pet food causes high incidences of periodontal disease in domesticated cats and dogs. Still, research has found that foxhounds fed with raw diets, including raw bones, had various levels of periodontal disease and a high rate of tooth fractures.

Since many dog owners believe that feeding their dog raw bone is a good approach to take care of their dog's oral health, most persist in feeding these. With this, the safest bone to give is a bovine femur, which is uncooked, uncut, and larger compared to the pet's mouth. On the other hand, chewing on marrowbones is often discouraged by veterinarians owing to the possibility of tooth fractures and zoonotic disease transmission.

Despite extensive study on passive dental home care, regular teeth brushing is still the most efficient method to minimize plaque and calculus buildup. Veterinary dentists believe that passive home care may supplement teeth cleaning but not a substitute.

Natural Tooth Wear on a Natural Diet

Orfeo's, 10 years old, tooth wear from chewing bones:

Darcy, 6 years old, showing wear on the canines.

Chewing

Chewing products may assist in decreasing the severity of gingivitis by cleaning tooth surfaces mechanically; however, dogs provided with dental chews still had plaque buildup and gingivitis. Thus, the rate of decrease is insufficient to avoid the formation of calculus, leading to gingivitis then periodontitis, even in dogs fed dry food.

As a result, adding substances to meals that give dental advantages by chemically affecting the development of dental plaque or calculus throughout the oral cavity is another option. Polyphosphates, which affect the formation of dental calculus, is a type of chemicals that have been demonstrated to be beneficial.

Different results connected with various chew toys and the impact on mandibular and maxillary teeth indicate that dog owners should give their dogs a range of chew products. The effect is cumulative by feeding dry food and adding several chew toys.

Dogs provided with dry kibbles should have at least one option for chewing. When a dry diet is combined with regular access to chew toys, the combined effect may exceed a "chewing threshold" that provides some amount of protection not attainable when canned or soft food is served with minimal chance to chew. It's also likely that dogs that eat dry pet food are more frequent "chewers" by nature or training. In addition, dogs grouped as slow chewers had less calculus buildup than fast chewers.

Food Texture and Kibble Size or Shape

In the oral environment, food texture and kibble properties can regulate dental plaque and possibly reduce the incidence of periodontal disease. Factors like food size, shape, density, and moisture content are thought to be essential. Theoretically, if the form and size of the kibbles are suited for pets and the size of the animal's mouth, dry food might mechanically reduce plaque. The texture must enable teeth penetration deep into the kibble before breaking or crumbling, and its size must encourage chewing before swallowing to maximize mechanical cleaning.

Dental Diets and Biscuits

Dry food and chews are thought to minimize the formation of plaque and gingivitis but not prevent it. While mechanical abrasion may help reduce plaque on chewing surfaces, it may be ineffective on non-chewing tooth surfaces in the mouth.

Dental diets

Compared to regular pet feeds, various commercial dry diets for adult dogs have been developed with greater oral cleansing capabilities. A kibble with a bigger size and texture, which stimulates chewing and increases contact with the teeth, provides the mechanical action of these feeds, thus providing control to plaque, stain, and calculus formation.

The kind of fiber in dental diets is also suggested to help gums exercise, promote gingival keratinization, and clean the teeth. One thing to remember is that, although these products may help to reduce plaque and calculus, they are most effective near the cusp tips rather than at the gingival border.

The teeth dig into the kibble before it breaks if the diet is structured correctly. The fiber in the kibble softly abrades the tooth surface as the tooth penetrates the kibble, eliminating plaque. Some dental foods have been demonstrated in studies to give considerable plaque, calculus, and stain management in dogs, particularly when used in conjunction with dental prophylaxis.

Dental treats

Simple baked biscuit treats and chews toys, such as string and rope toys, have not been proven to help prevent periodontitis; however, there is evidence for the effectiveness of dental chews produced from compressed wheat cellulose included in treats and rawhide chews.

As previously stated, chew-based treatments do not adequately clean the canine teeth and incisors. A recent entrant into this field includes delmopinol, an anti-plaque chemical dispersed throughout the mouth and may have beneficial effects on these teeth. This product also has a consistency that enables teeth to chew the whole treat, effectively cleansing the gingival edge. Also, there is proof that this substance aids in managing halitosis.

Risks of dental chews

- Esophageal foreign body obstruction

- Tongue entrapment

- High calorie which can lead to weight gain and obesity

- Gastrointestinal upset

- Tooth fractures (antlers, hooves, nylon bones)

- Especially lower fourth premolar

- To check excessive hardness: the ability to dent the treat with a fingernail or willingness to be hit on the knee with the treat

Additives

Antiseptics or additives are used in specific diets and snacks to slow or prevent plaque or calculus formation. Sodium hexametaphosphate, HMP, forms soluble complexes with cations such as calcium and reduces the amount of calcium available for calculus formation. HMP supplementation to a dry meal reduced calculus in dogs by approximately 80%, yet, tartar is not a critical factor in the development of gum disease. Also, animals with overt or preclinical renal illness may be concerned about the quantity of salt and phosphorus in HMP.

Antiseptics added to meals or water additives are an appealing way for treating periodontal disease. On the other hand, plaque bacteria are resistant to antiseptic concentrations up to 500,000 times those that would kill a single bacterium. As a result, although the chemical may benefit some bacteria, it is usually inadequate to reduce plaque.

Chlorhexidine is an oral antiseptic that may decrease plaque, notably as a perioperative or pre-prophylaxis rinse, while it may also increase plaque mineralization to calculus. Using as a rinse, however, may not achieve adequate contact time.

Vitamin and Mineral deficiencies

Gingival illness has been linked to vitamin A, C, D, and E deficiencies, and deficiencies in the B vitamins folic acid, niacin, pantothenic acid, and riboflavin. Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, which may lead to periodontal disease, can be caused by calcium-deficient diets.

Probiotics

In human periodontitis, nitric oxide (NO), a major inflammatory mediator, is elevated; however, limiting its production or effects might be beneficial. Lactobacillus brevis is a probiotic bacterium rich in arginine deiminase. High amounts of arginine deiminase compete with nitric oxide synthase for arginine substrate inhibiting nitric oxide synthesis.

The topical use of probiotics containing L. brevis reduced inflammatory mediators implicated in human periodontitis. In relation, preliminary research on dogs revealed that topical L. brevis CD2 reduced gingival inflammatory infiltrates.

Prevention

Recommendations for young patients include the following:

- Examine all deciduous teeth for missing, unerupted, or slow-to-erupt teeth. It is also recommended to check for irregular jaw length and teeth touching other teeth or soft tissue since early extraction may be required.

- Retained deciduous teeth must be addressed when permanent teeth begin to develop. Permanent teeth may be displaced by the persistent deciduous teeth, causing malocclusions and crowding, leading to periodontal disease. In situations of unstable dentition, extraction of deciduous teeth without replacing permanent teeth might be essential. Unerupted permanent teeth in young dogs should be checked using intraoral dental radiography.

- Owners with pets that have erupted permanent teeth may start home oral hygiene training. Young pets may experience discomfort when changing teeth and may associate dental home care with a negative experience.

- Puppies smaller than 20–25 lbs at maturity will require a higher level of dental care and prevention; thus, owners should be informed. Also, brachycephalic breeds are prone to have more dental problems because of crowding and rotation of teeth.

- It is recommended to have dental prophylaxis at the age of one for small to medium breeds and the age of two for large breed dogs. This includes dental cleaning, polishing, and dental radiographs are necessary.

Periodontal disease with attachment loss may be addressed by a comprehensive dental exam, intraoral radiographs, cleaning and polishing, and any required therapy.

Prevention of Dental Disease and Home Maintenance Care

Regular and consistent preventative dental care cannot be replaced by feeding dry food or formulated oral care diet. Regular home care, periodic veterinary dental prophylaxis, and the supply of adequately selected and various chewing materials for dogs are the fundamental approaches for avoiding the development of gingivitis and periodontal disease. A dry or an oral care diet can support these therapies.

Veterinary dental prophylaxis includes supragingival and subgingival scaling and polishing, performed under general anesthesia. Scaling eliminates plaque and calculus from above and below the gingival contact. Treatment frequency is determined by the pace of plaque formation, the degree of gingivitis or periodontal disease present, and the pet's age. The danger of repeated anesthetic administration must always be addressed since moderate to severe dental disease is most typically encountered in elderly dogs and cats.

Dental cleaning is advised every 12 to 18 months for dogs with healthy gingiva. Prophylaxis should be done more often in pets with persistent gingivitis or periodontitis, generally every 6 to 12 months. Owners must understand that even if their pets have consistent home dental care, periodic dental cleaning is still required when the pets have developed a dental disease. Although regular teeth brushing may efficiently remove plaque, it has little influence on the severity of subgingival disease and may even disguise disease development below the gingival surface. As a result, routine and ongoing expert care are required for dogs diagnosed with periodontal disease.

The most effective way of dental care is regular teeth brushing at home. Brushing the teeth helps to reduce plaque buildup and gingivitis. According to current research, the frequency of brushing required to maintain clinically healthy gingivae is dependent on the dental condition.

Providing a range of chew toys and products for dogs and providing dry food can be additional care. Wet food with no opportunity to chew hard kibble or biscuits should be avoided unless a health issue necessitates the usage or the pet refuses to eat dry kibbles. If a pet's diet consists mainly of wet or canned food, regular dental cleaning, chew toys, and dental prophylaxis are all essential.

References

- Bellows, J., Berg, M. L., Dennis, S., Harvey, R., Lobprise, H. B., Snyder, C. J., Stone, A. E. S., & Van de Wetering, A. G. (2019). 2019 AAHA Dental Care Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 55(2), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6933

- Case, L., Daristotle, L., Hayel, M., & Raasch, M. (2011). Canine and Feline Nutriton: a resource for companion animal professionals. Mosby Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-39175-8

- Enlund, K. B. (n.d.). Dental care in dogs: A survey of Swedish dog owners, veterinarians and veterinary nurses. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science Department of Clinical Sciences. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Gorman, G. (2012). Practical dentistry for veterinary nurses. Annual Conference of the New Zealand Veterinary Nursing Association.

- Niemiec, B., Gawor, J., Nemec, A., Clarke, D., McLeod, K., Tutt, C., Gioso, M., Steagall, P., Chandler, M., Morgenegg, G. & Jouppi, R. (2020), World Small Animal Veterinary Association Global Dental Guidelines. J Small Anim Pract, 61: E36-E161. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13132

- Perrone, J. R. (ed.) (2013). Small Animal Dental Procedures for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Responses