Simona Cafazzo, Martina Lazzaroni, and Sarah Marshall-Pescini - published in 2016

This information is based off a few decades of accumulated research, but is scaffolded mainly from Rudolph Schenkel's work in captive wolves and David Mech's work on free living wolves.

ABSTRACT

Background: Dominance is one of the most pervasive concepts in the study of wolf social behaviour but recently its validity has been questioned. For some authors, the bonds between members of wolf families are better described as parent-offspring relationships and the concept of dominance should be used just to evaluate the social dynamics of non-familial captive pack members (e.g., Mech & Cluff, 2010). However, there is a dearth of studies investigating dominance relationships and its correlates in wolf family packs.

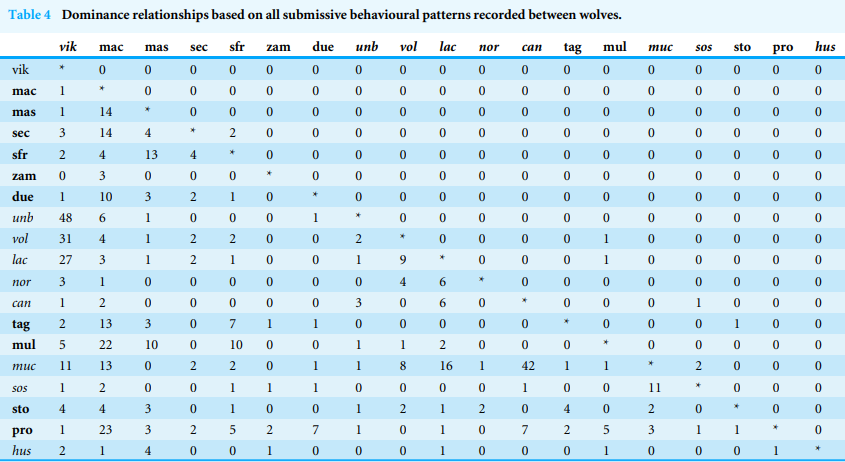

Methods: Here, we applied a combination of the most commonly used quantitative methods to evaluate the dominance relationships in a captive family pack of 19 Arctic wolves.

Results: We found a significant linear and completely transitive hierarchy based on the direction of submissive behaviours and found that dominance relationships were not influenced by the competitive contexts (feeding vs. non-feeding context). A significant linear hierarchy also emerges amongst siblings once the breeding pair (the two top-ranking individuals) is removed from analyses. Furthermore, results suggest that wolves may use greeting behaviour as a formal signal of subordination. Whereas older wolves were mostly dominant over younger ones, no clear effect of sex was found. However, frequency of agonistic (submissive, dominant and aggressive) behaviours was higher between female–female and male–male dyads than female–male dyads and sex-separated linear hierarchies showed a stronger linearity than the mixed one. Furthermore, dominance status was conveyed through different behavioural categories during intra-sexual and inter-sexual interactions.

Discussion: Current results highlight the importance of applying a systematic methodology considering the individuals’ age and sex when evaluating the hierarchical structure of a social group. Moreover, they confirm the validity of the concept of dominance relationships in describing the social bonds within a family pack of captive wolves.

-

Linear and Transitive

-

Heiracrchy is present although there are fewer demonstrations compared to interactions with the breeding pair.

-

Definite corralation with generation and dominance (consider wolf generations are seperated by years)

-

Breeding pair have lax heirachy, males and females MOSTLY concerned with heirachy of same sex, but there is a heirachy between sexes that is not determined by sex

-

Females and males tend to enforce heirchy differently (females use more aggression toward each other)

-

Still true - Formal submissive greeting are still a good indicator of rank and submissive behavior is still the most commonly expressed and accurate way to determine rank

Hence, in the current study we applied a combination of the most commonly used quantitative methods to evaluate dominance relationships, in order to investigate (1) whether an agonistic dominance hierarchy could describe the relationships between members of a captive family pack of Arctic wolves and whether a hierarchical structure would remain consistent (amongst siblings) when the top-ranking individuals (i.e., the breeding pair) were removed from analyses (see Shizuka & McDonald, 2015); (2) whether the hierarchy remained consistent in a feeding and non-feeding context; (3) which behaviours may be the best indicators of dominance (4) whether mouth licking associated to tail wagging (greeting, hereafter) can be considered a formal signal of submission in wolves, as has been found in dogs.

Finally, to help address the controversy regarding the validity of the dominance concept in wolves, we also aimed to assess (5) if the typical age- (and sex)-graded model could adequately describe the relationships of the nuclear family pack of wolves observed.

Which behavioural category is the best indicator of dominance relationships?

Can greeting behaviour be considered a signal of formal submission?

Does the rank order in our pack conform to the ‘age-(sex)-graded’ model?

Overall, dominance relationships appeared to be influenced by age, with older wolves being dominant over younger individuals, but not by sex.

Male hierarchical relationships appeared to be based on dominance and submissive behaviours, while female hierarchal relationships appeared to be based on aggressive and submissive behaviours.

DISCUSSION

Using linearity (De Vries, 1995), triangle transitivity (Shizuka & McDonald, 2014) matrixranking procedures (MatMan; (De Vries, 1998), and taking into account both the sex and ages of the wolves in our pack, we found:

(1) the existence of a clear linear hierarchy unaffected by the competitive context and which remained solid also when the highest ranking individuals (the breeding pair) were removed from analyses,

(2) evidence suggesting the use of ‘greeting’ as a formalised signal of subordination, and

(3) partial support for the age-(and sex)-graded model

Agonistic dominance relationships in the presence and absence of food

The main result of the current study is that the relationship between family pack members of the Arctic wolves studied were not randomly distributed but rather, showed a high linear, transitive, and significant hierarchy, which remained constant across both the feeding and nonfeeding contexts. Furthermore, we found that the best indicator of dominance, which resulted in the clearest hierarchical relationship between individuals was the direction of submissive behaviours (e.g., crouch, passive and active submission, flee, etc.). The breeding pair was involved in most of the interactions, as previously reported also in other captive and wild packs (e.g., Van Hooff & Wensing, 1987; Mech, 1999), and although Shizuka & McDonald (2015) point out that linearity of a hierarchy may be ‘skewed’ due to dominant individuals showing more behaviours than the rest, this was not the case in our study. Indeed results showed that a linear and completely transitive hierarchy based on submissive behaviours was still highly significant when the two top-ranking individuals were removed from the analyses. These results indicate that clear dominance relationships exist among all siblings and confirm submissive behaviours as a more reliable indicator of hierarchical relationships in the pack than aggressive and dominance behaviours.

Why is this signigicant to us as dog trainers?

Although the common social structure in wild wolves is usually made up of the reproducing parent pair and their offspring of the last two years, ranging from two to 15 individuals (e.g., Bloch, 2002), families composed of several generations of up to 19–26 individuals (e.g., Landau, 1993; White, 2001; VonHoldt et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2012),

have been described. Hence our pack of Arctic wolves, composed of five generations and a total of 19 individuals, can be considered representative of a multigenerational family pack of wolves. Therefore, the clear presence of a linear hierarchy in our family pack of wolves goes against recent suggestions that hierarchical relationships may only be adequate to describe atypical pack structures such as disrupted families or forced packs of unrelated individuals (Mech & Cluff, 2010) and rather supports the importance of this concept also in describing the relationship between wolves in a multi generational family pack.

Compare to Mech which only recognized between age/sex

. A further confirmation of the importance of dominance relationships in wolves comes from our second finding, that such relationships remained constant across competitive and non-competitive contexts. Indeed the dominance and submissive rank orders detected in the presence of food were highly correlated to the respective rank orders detected in the absence of food. The slight differences observed between the two contexts may be explained by the high percentage of null dyads (Van Hooff & Wensing, 1987). Indeed, when adding together all submissive and dominant interactions occurring in the two contexts, we found improved values of linearity and unidirectionality for both hierarchies, further indicating that dominance relationships in our family pack were not influenced by the competitive context. In some mammal species, it may be reasonable to predict the existence of asymmetries in fighting abilities and resource value, especially between different age-sex classes, leading to different rank orders in different contexts. Indeed, food is considered a major determinant of the reproductive success of individuals hence, in species where females play the main role in rearing pups food should have a higher value for them than for males, leading to a female over male dominance hierarchy during feeding competition but not in other contexts. This has been found to be the case in both chimpanzees and cats, where females raise their infants largely with no male intervention (e.g., chimpanzees, Noë, De Waal & Van Hooff, 1980; domestic cats, Bonanni et al., 2007). However, wolf packs rely on cooperation between all pack members in both rearing pups and providing food; this may account for the consistency of dominance relationships and the absence of a diverse effect of sex in the feeding and non-feeding context.

Submissive behaviours best fulfilled the criteria of agonistic dominance indicators since they showed a higher linearity, a complete transitivity, and rank orders with no inconsistencies. The importance of submissive behaviours in establishing and maintaining dominance relationships have been widely highlighted in primates (Rowell, 1974; De Waal & Luttrell, 1985) but also in wolves (Schenkel, 1967; Mech, 1999). In our pack, subordinate individuals often determined the outcome of agonistic interactions by lowering themselves when being approached by or when approaching dominant individuals, as described in wild wolf interactions (Mech, 1999). Similar results have also been found in other captive family packs (Van Hooff & Wensing, 1987; Romero et al., 2014). In sum, to date the results suggest that submissive behaviours play a more relevant role than dominance displays in terms of maintaining dominance relationships between all members of a family pack, although further investigation should assess the importance of submissive behaviours in promoting friendly relations and pack cohesion in wolf pack, as has been suggested by some authors (e.g., Mech, 1999).

Greeting as formal indicator of submission

Overall our results showed that greeting in Arctic wolves partially fulfilled the criteria of a formal signal of submission, although it occurred only in a limited number of dyads, it was almost completely unidirectional and it was exhibited in line with the agonistic dominance hierarchy, in that it was displayed mainly by subordinate individuals towards dominant ones. The main exception was the breeding pair, in which this behaviour was exchanged equally. This is particularly interesting considering that their relative position in the hierarchy was also not always fixed; the male appearing dominant over the female when calculating the rank based on dominance displays and vice versa when basing the rank on submissive behaviours. This might indicate a relaxed dominance relationship between breeding partners, with the females prevailing in some situations and the male in others, as described in other captive family packs (Van Hooff & Wensing, 1987) and wild packs (e.g., Mech, 1999).

The age-(sex)-graded model

In our pack we found an overall dominance hierarchy based on submissive behaviours in which males were not, on average, higher in rank than females, but older wolves were dominant over younger ones (with the exception of two adult males who ranked at the bottom of the hierarchy). In wild wolf packs, it is usually reported that all members submit to the breeding pair, and the breeding female to the breeding male, with no clear dominance displays being observed between offspring (Mech, 1999; Bloch, 2002). In captive studies, males are mostly described as being dominant over females and older individuals over younger ones (e.g., Van Hooff & Wensing, 1987; Romero et al., 2014).

However, differently from the current study, previous work both in captivity and in the wild never statistically tested the effect of sex and age. Our results support the effect of age, showing largely that older siblings are dominant over younger ones, but do not support a sex effect of males being dominant over females. Interestingly however, when looking at the frequency of the three main behavioural categories used to calculate dominance relationships in our pack, we found that female– male agonistic interactions were fewer compared to intra-sexual (female–female and male–male) agonistic interactions. In other words, although an overall hierarchy including animals of both sexes was detected, agonistic displays were not so frequently expressed in interactions between females and males. In fact, females showed agonistic behaviours preferentially towards other females and males towards other males. Taking into account this differential pattern of behaviours, we calculated sex-separate linear hierarchies, which, in both cases, showed stronger linearity than the mixed hierarchy. Moreover, dominance relationships appeared to be expressed making use of different behavioural categories in male’s and female’s hierarchies. The best hierarchies (in terms of unidirectionlity, linearity, and transitivity) in females were based on aggressive and submissive interactions, whereas in males, hierarchies based on submission and dominance behaviours showed better indices. Taken together, results suggest that although the pack as a whole shows a clear hierarchical organization, the structure of the hierarchy within each sex is even clearer. Furthermore, it appears that females and males may use different ways to communicate their reciprocal rank when interacting with members of their own sex. Van Hooff & Wensing (1987) found similar results in a family pack of European wolves, where intra-sexual relationships were characterized by a higher intensity of exchange of agonistic behaviour than inter-sexual relationships. An unexpected result is that females, but not males, appeared to use aggression to communicate their reciprocal status in interactions with other females. This result disagrees with most of the studies on hierarchies outlining submission as the best measure of dominance relationships (e.g., Rowell, 1974; Bernstein, 1981; Hand, 1986; Cafazzo et al., 2010. A potential explanation is that in general, aggressive interactions were frequent between individuals of our study pack, potentially due to the data being collected mostly during the breeding season, which starts in January and lasts approximately until April. During this time the hierarchical structure of the pack likely regulates breeding activity, and aggressive interactions may be used to more forcefully maintain the status among individuals. Further studies are needed to ascertain whether indeed the behaviours used to maintain the hierarchy are different during breeding and non-breeding periods. The greater linearity of the hierarchical organization and the differential patterns of behaviours used to maintain it in males and females raises the question about the most appropriate way to characterize the dominance relationships among members of a wolf pack. Are sex-separate hierarchies a better model than all-member hierarchies to describe such relationships? Several authors suggest that separate same-sex hierarchies best describe the social structure of wolf packs (Schenkel, 1947; Rabb, Woolpy & Ginsburg, 1967; Zimen, 1975; Zimen, 1978; Derix et al., 1993; Derix & Vanhooff, 1995). Nevertheless Zimen highlighted the existence of an overall hierarchy with males being dominant over Cafazzo et al. (2016), PeerJ, DOI 10.7717/peerj.2707 18/24females in each age class, which is also the usual model reported in studies of wild wolves (Clark, 1971; Mech, 1999). Unfortunately, as stated above, most of the previous studies carried out both in captivity and in the wild, did not follow a systematic procedure aimed to statistically show the dominance relationships in the pack, which makes a comparative assessment of results difficult. Based on current results, when considering the pack as a whole the hierarchical structure does not show males being dominant over females, but given the stronger linearity indices of separate male and female hierarchies, it would appear that status within sexes may carry an even greater weight than within the mixed sex group.

A final point to consider is the validity of captive-based studies when attempting to characterize the social structure of a wild species. It is undeniable that studies with wild animals are preferable when exploring such topics; however, it is perhaps interesting to note that in a metanalyses involving 113 studies looking at dominance structures in 85 species (172 groups), Shizuka & McDonald (2015) found that whether studies were conducted in the wild or in a captive setting did not affect results. With such elusive species as wolves, partial reliance on captive studies is probably unavoidable, however future research using the same methodologies adopted here on wild animals would be particularly important to further our understanding of wolves’ social behaviour.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we emphasize the importance of applying a systematic methodology including both age and sex in order to analyse dominance relationships between pack members. Results clearly show that both within each sex and for the pack as a whole, dominance relationships are a meaningful concept, which can be used to describe the structure of a multi-generational family pack of captive wolves. Future studies analysing the potential effects of dominance relationships on other aspects of the animal’s lives will likely help to further establish the importance of this concept to describe the social lives of wolves.

Take Aways as a Dog Trainer

-

Misunderstanding "dominance" and using it as a physical training technique is at least 20 years out of date

-

Misunderstanding "dominance" and claiming it isn't relavant behavior or doesn't exist is ALSO out of date (this study is 2016, but studies have been misterpretted since 1999 and earlier).

-

Normal vs abnormal behaviors when doing evaluations

-

circular/non-linear/etc..

-

dominance conflicts with young dogs

-

conflicts with same sex/age

-

intact breeding age dog conflicts (especially with females)

-

Humans playing the role of leader may reduce and show less expressions in "lower ranks".

-

Reminder that resource guarding falls outside this scope.

-

Responses